How transit can make public space disappear

The Gezi Kitchen during the 2013 protests, courtesy of Arkitera. Click photograph for more and source.

In class earlier this week, we spoke about public space and protest, which necessarily brought up the Gezi Park protests in 2013. There was a lot written back then, and through the past several years, about the park. Also about land use in Istanbul, politics and public space in Turkey, and a zillion other related things. Gezi could signify whatever one wanted it to signify, for a certain period of time.

For someone like me, who first came to Istanbul as a college kid in 2007 (a decade ago! My word!), Gezi is waiting for my bus. It’s grabbing a tea next to a cadre of old men chain-smoking and it’s hanging out in the sun or ducking from the cold.

The young author and a younger puppy.

I have lots of fond memories, is what I’m saying. I remember playing with an exuberant Samoyed puppy named Pamuk, watching a weird Festival of Nations Tatarstani dance troupe do the Benny Hill theme song. A Karadeniz Günleri festival where they were handing out free samples of a variety of teas to show off the terroir. I remember scarfing a cheese, onion and pickled pepper sandwich while waiting for the 42T to take me back to Arnavutkoy. As I said, fond memories.

Gezi Park still exists, nominally, but Taksim Square’s been redone. The government undergrounded roads and changed the bus circulation to make it more pedestrian-friendly (I suppose) but removed any reason to sit and linger in the public space.

Images of Taksim Square in the 1960s(?), showing bus service (L, via kultur servisi) and today, without busses (R, via YouTube/recep alanoglu)

None of this is terribly new to the internet, my own personal soliloquy aside. What’s interesting to me is the second half of how Gezi Park was sidelined in Istanbul life: Istanbul got a whole new transit system.

The Istanbul of 2007 had bus-focused transit and Taksim was the beating heart of the bus system. This was a big part of traffic congestion to be sure, but one could reliably meet anyone on the European side in Taksim Square — and kill time in Gezi Park while waiting for them to arrive. Even the ferry boats, taxis and dolmuşes were plugged into this system (which, fascinatingly, was in many ways an above-ground mirror of Istanbul’s water system…but that is another blog post in the future).

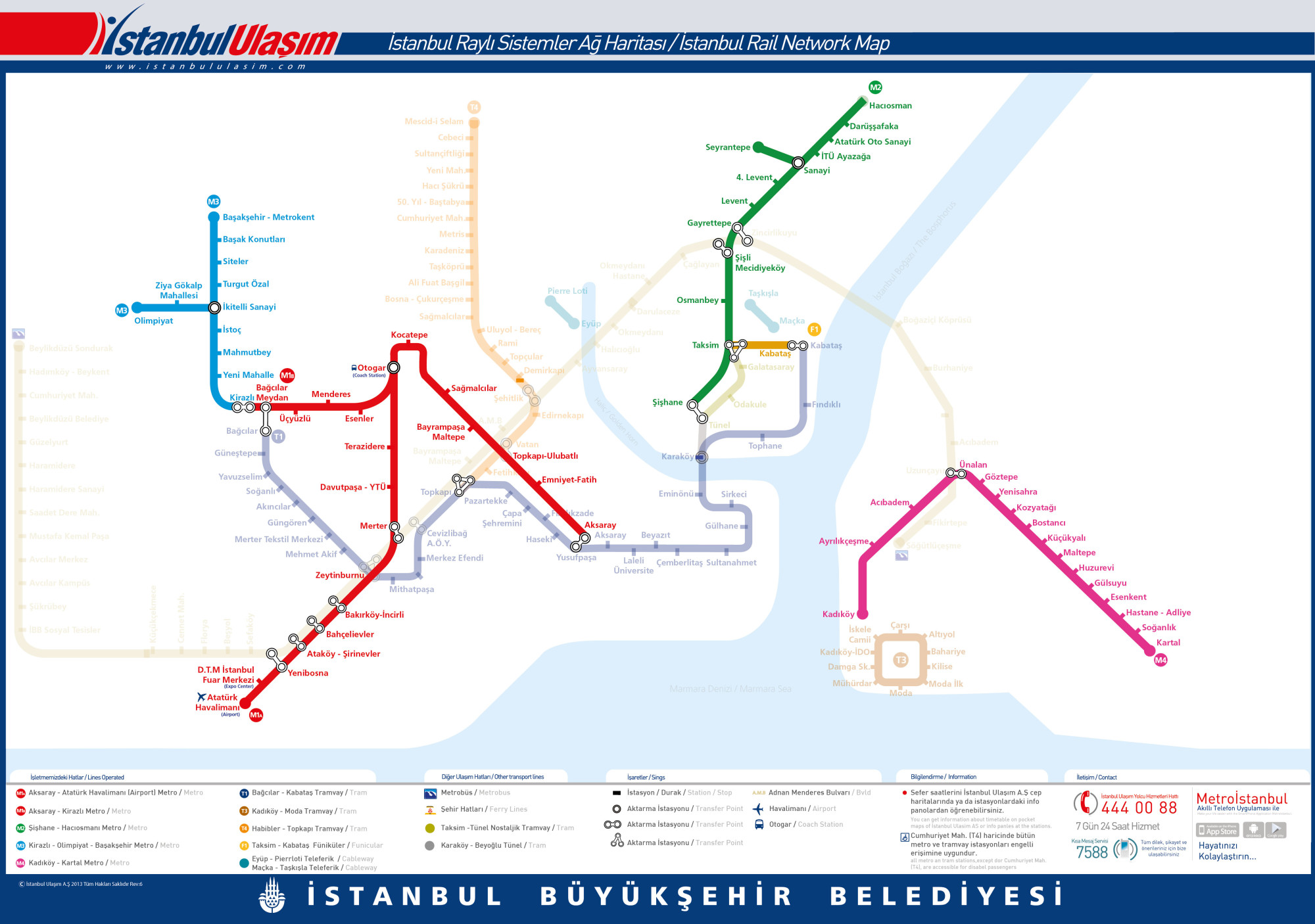

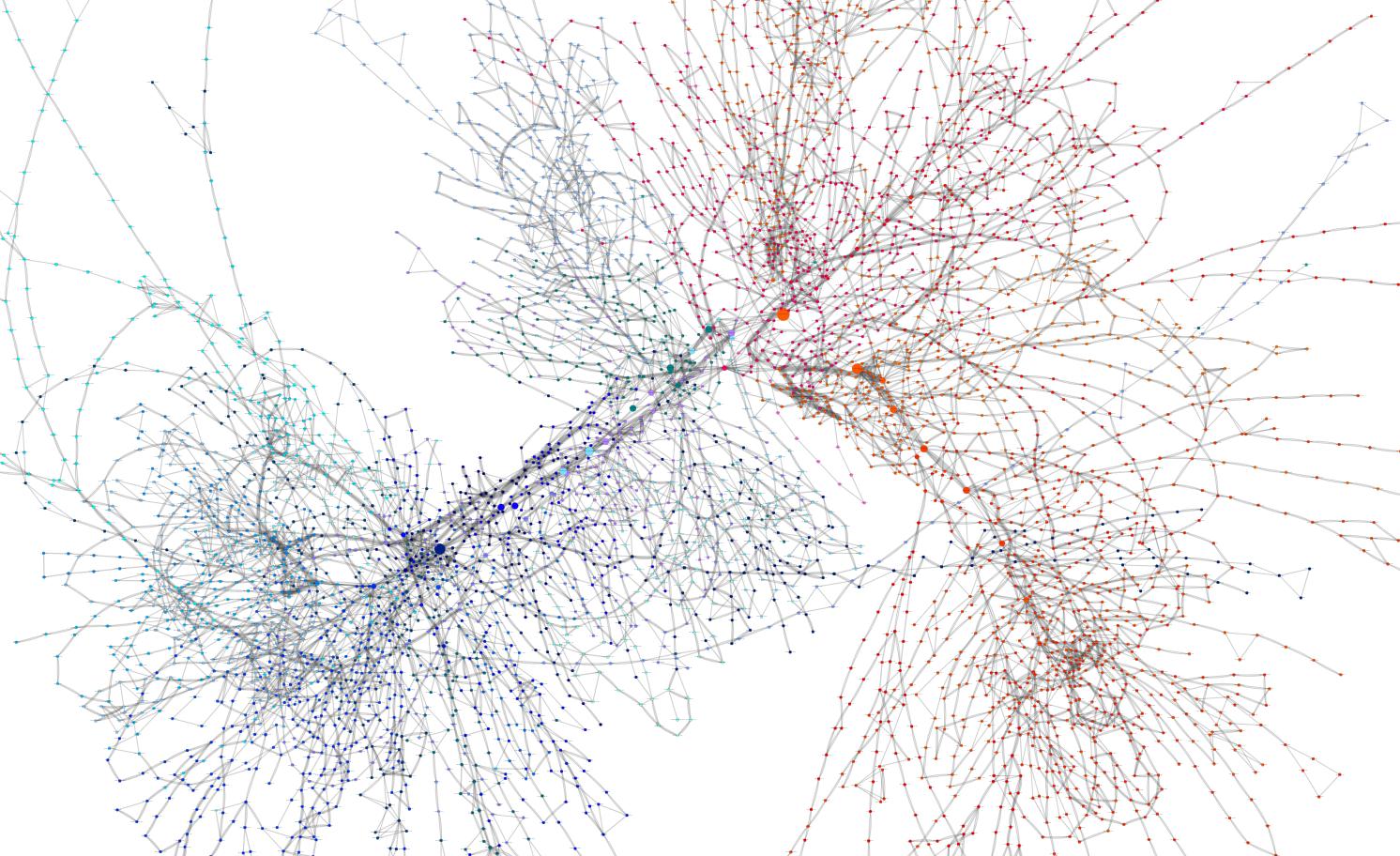

Istanbul Metro lines in 2013 and a visualization of Istanbul bus lines in 2013 (via SayaSaya). The two images are not to scale, but show Taksim's centrality.

By the 2011 elections, however, the ruling AKP party was billing itself as the party of giant infrastructure projects. This was before they got crazy — no third bridge yet, no third airport, no bonkers canal. But the Marmaray subway between Europe and Asia was underway. And all over the city there were billboards proclaiming how quick it now was to get from one end of Istanbul to the other.

A 2015 advertisement: "Metro from everywhere, to everywhere". Via Latin for Honey.

It was really effective! As Istanbul kept on growing, a rail system made it easy to get everywhere. Not just from the airport to the tourist sites to Taksim, as in the old rail lines, but through out tons of neighborhoods that were popping up seemingly overnight. As someone who went back to Istanbul every few months, or every year, it was astonishing to see the “this line coming soon” dotted lines on the transit map get filled on.

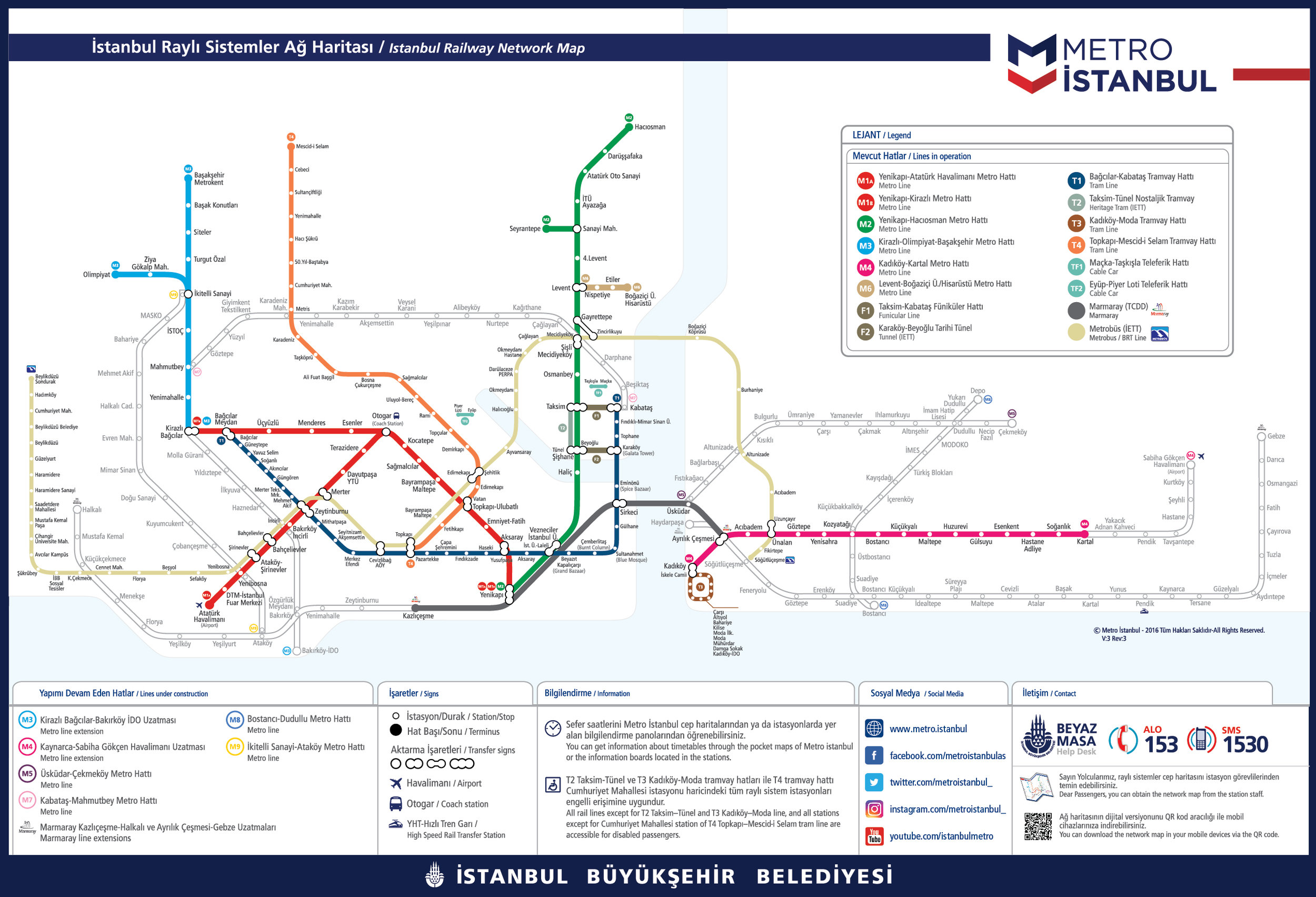

One thing about the new transit system is that it de-centralized Taksim. Looking at the transit map of today, all roads lead to Yenikapı.

The 2017 Istanbul Metro map. Yenikapı is at the bottom center, where the red, green and grey lines converge. Compare to the 2013 map above.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with Yenikapı. It’s close to the tourist sites (which is useful for the non-tourists who work there) and connects boats with the Marmaray tunnel with the highways with the rails, which is good for redundancy. It is also in the Fatıh neighborhood, which votes reliably for AKP. That probably isn’t a coincidence, but it also is not a shock. Lots of places, even in Istanbul, are AKP strongholds.

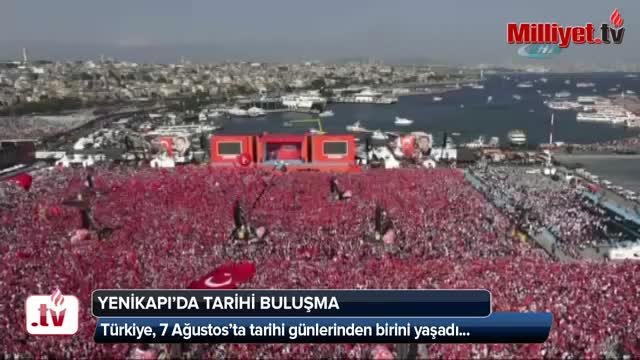

As part of the Yenikapı expansion, the neighborhood even got a whole new Event Area. It has been, unkindly, likened to a tumor:

The Yenikapı meeting place under construction, via Arkitera. This was where the major post-coup attempt rallies were held — travel on public transit was made free.

This is now the main political square of Istanbul. Huge rallies are held in Yenikapı for a lot of the same reasons they used to be held in Gezi (it’s easy to get there from everywhere, and there’s a lot of open space once you’re there) plus one big new one: the government really wants to hold rallies there. The space is also surrounded on three sides by water, so good luck dispersing from the police even if you wanted to!

I am probably hedging more into political/critical writing than I really want to here. I miss the old Taksim, and I also realize that pretty much every city is at its best in nostalgic light. I don’t have to live in Istanbul, I never voted in Turkey, and I speak less and less Turkish by the day.

The point I want to emphasize with this is how much transit and public squares build off of one another. When the Turkish government wanted to de-emphasize Taksim, they routed their huge infrastructure through a different neighborhood. This wasn’t done in the hazy past but in the past decade, under recent memory and during political fracture.

And now it’s done. The TV cameras circle Yenikapı during a big political event and Taksim is somnolent — to go along with the gutting of Istiklal (link to that 140 journos on Istiklal neoliberalism bit), which was 10 million people’s main street for the past 100 years.

When we talk in class about what planners do, it’s often framed as apolitical best practices. And absolutely, some times it is. But it’s fascinating to look at how urban planning was an integral part of Turkey’s profound political shift in the past couple decades, and how any such shift could (or should) be implemented in the future.